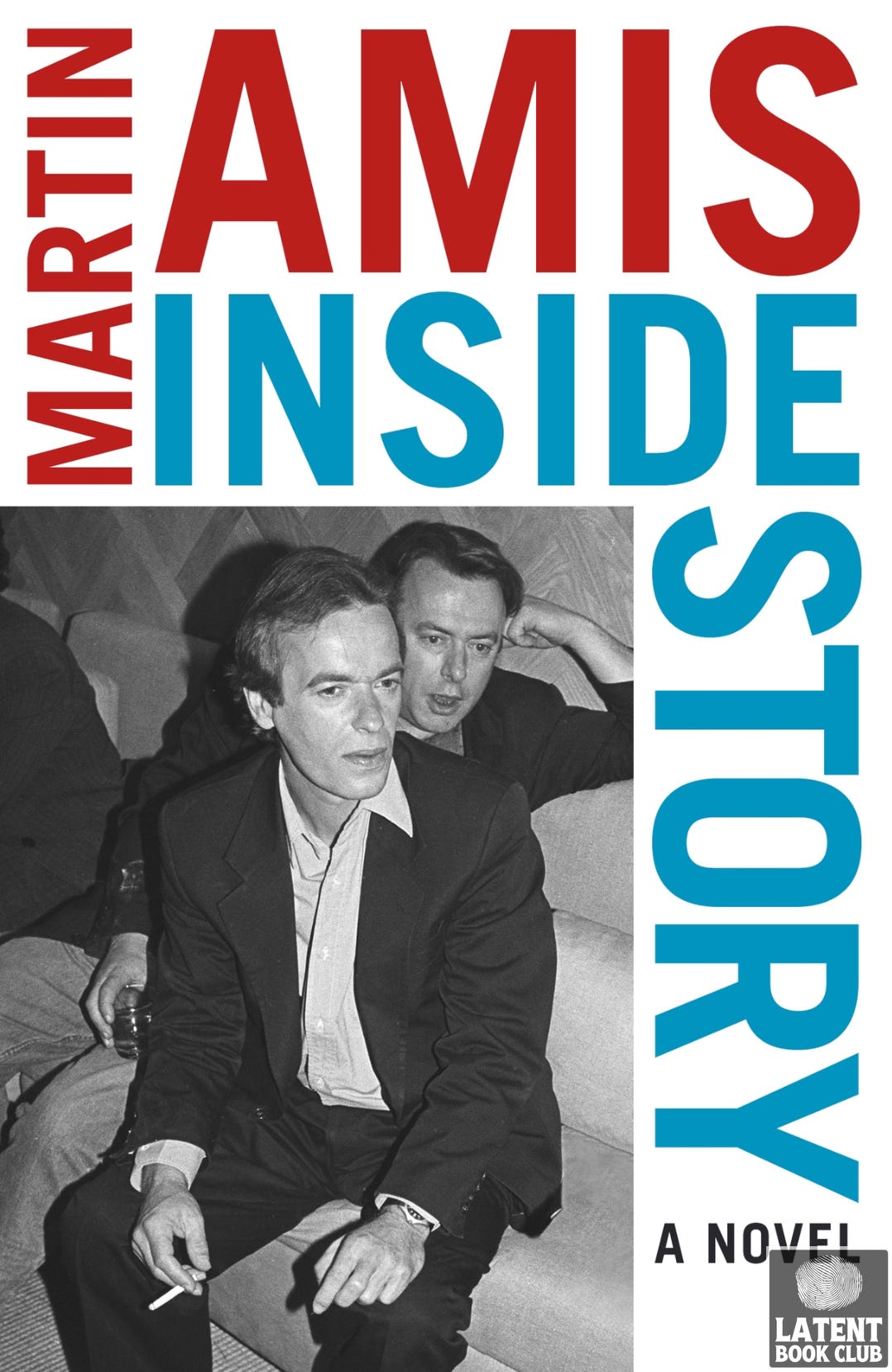

The Latent Book Club explores Martin Amis’ final work, Inside Story: a baffling and slightly confused memoir/fiction: a roman à clef where you are certain you possess the keys, but aren’t quite sure which doors they open.

Inside Story is a quality, if at times baffling and oddly recondite work. It will be the book we always remember as, much to our intense sadness, Martin Amis died while we were reading it. And bidding a farewell to a hero is never easy, notwithstanding the strange comfort to be taken from a book which itself feels like a goodbye.

Why baffling? Well, it’s part autobiography. One part fiction - and a strangely sexual, introverted and infatuated one at that. Another part theory on how to write, and a further part on what it is to read well, and understand what quality is in the written word. And finally, without trying to be one, indeed while denying it is one, Inside Story, if it is any one thing, is a panegyric to one of Amis’ best friends, Christopher Hitchens.

without trying to be one, indeed while denying it is one, Inside Story, if it is any one thing, is a panegyric to one of Amis’ best friends, Christopher Hitchens.

It is probably one of our most highlighted books due to the smorgasbord of literary theory, writing, and close-reading tips it holds. And that alone makes this lengthy (520ish pages) tome worth the price of admission.

The first take-away from the book: always look up unfamiliar, or even familiar words. Drill right down into the etymology of the thing. The root of a word always has something to teach, be it Latin, Greek, Arabic or beyond. Only when we do so can we be assured of what we mean. There is joy, precision and poetry at the heart of the art of being a writer.

Amis has written autobiography before - Experience - which is well worth reading. But what sets this apart is the levels of involution throughout. Because it is part autobiography and part fiction, you are often left questioning whether which part you are reading.

No place is this more obvious than the significant portion of the book dedicated to Phoebe Phelps. Phelps is an interesting character, and certainly made the first portion of the book compelling, as you are left wanting to know what happens to Amis and Phelps’ romance, particularly since it is clear they are a terrible fit for one another.

Phelps herself is a pastiche of some of the significant women in Amis’ life, interspersed with fiction - but we had to google that part to discover it, and we doubt very much we will be the only ones.

Phelps herself has several sides to her. One is anachronistic - this daughter of a washed out Lord who is formally introduced to Amis in a setting that almost seems from a period drama, or perhaps at the best an early 80s tele-drama. One is absurdly sexual - Phelps is a lustful character, in the sense that she is both lusted after and arouses lust in Amis - the sexual side of her is surprisingly difficult to deal with as a reader. The other is her character arc - a rise and fall that mirrors Amis’, really, except in one obverse direction that this review will not spoil.

We loved the introduction, where Amis is settling you in, making you - a stranger - welcome to the inside story. This is how it starts:

“The book is about a life, my own, so it won’t read like a novel – more like a collection of linked short stories, with essayistic detours. Ideally I’d like Inside Story to be read in fitful bursts, with plenty of skipping and postponing and doubling back – and of course frequent breaks and breathers. My heart goes out to those poor dabs, the professionals (editors and reviewers), who’ll have to read the whole thing straight through, and against the clock. Of course I’ll have to do that too, sometime in 2018 or possibly 2019 – my last inspection, before pressing SEND. Meanwhile, enjoy New York. And once again – welcome to Strong Place! Now, you take your drink, and I’ll take your bag. It’s no trouble. There’s a lift … Oh, don’t mention it – de nada. The honour is all mine. You are my guest. You are my reader.”

Has there been a more sublime introduction to a book? Probably, but not that there aware of.

Amis has some great things to say about life, and his experience from it. Some of the themes, as he entered his seventh decade, are surprisingly salutary. While Amis has been a critic, we have never taken him for a pessimist. And this is borne out by his sentiments throughout the book:

“You won’t believe this, but turning sixty, for men, is a great relief. To start with, it’s a great relief from your fifties. Of the seven decades: the thirties constitute the prince, the fifties the pauper. I assumed that my sixties would differ from my fifties only in being much, much worse, but I’m finding the gradient unexpectedly mild; in fact it embarrasses me to say that the only time I’ve ever been happier was in childhood. True, you have to deal with an uncomfortable new thought, namely: Sixty … Mm. Now this can’t possibly turn out well. But even that thought is better than nearly all the thoughts of your fifties (an epoch to which I will bitterly return)”

It’s almost impossible to condense all his pointers on how to be a writer, as they are suffused throughout the book, which no doubt merits a second or even third reading. Still, he has some cautionary topics for novelists, which are ‘naturally immune’ to being fictional successes including:

Dreams - Nothing odd will do long (Samuel Johnson)

Sex (the mechanics of it - all we usually need to know is how it went and what it meant)

Religion

What are suitable subjects for writing a novel about? Well, there’s plot for one:

“According to E. M. Forster (whom Jane used to refer to by his middle name, as did everyone who knew him), ‘the king died and then the queen died’ is a story, but ‘the king died, and then the queen died of grief’ is a plot. Not so, Edward, not so, Morgan! ‘The king died, and then the queen died of grief’ is still a story. To mutate into a plot, a story needs a further element – easily supplied, here, by a comma and an adverb. The king died, and then the queen died, ostensibly of grief is a plot. Or a hook. Plots demand constant attention, but a good hook can stand alone and untouched, like an anchor, and keep things fixed and stable in any weather. Plots and hooks yield the same desideratum: they set the reader a question, with the implicit assurance that the question will be answered.”

And making your important points at least simple for two:

“Mark my words: every piece of vital information has to be clearly stated in plain English; when it comes to inferring and surmising, readers have downed tools. The unreliable narrator (once a popular and often very fruitful device) has given way to the era of the unreliable receptor. The unreliable narrator is dead; the ‘deductive’ novel is dead.”

Amis adds that the slightly more esoteric experimental novels, such as stream of consciousness and unreliable narrators have entirely ceded to the hegemon, which is now social realism.

But, as he advises in Experience, some embellishment is required. Life is too thinly plotted, absurd and meaningless to be a satisfying basis for literature alone:

“D.H.L. failed to get anywhere much with ‘direct experience’, in my view. No one gets anywhere much with ‘life’. Its limitations are life’s limitations: poverty of incident, repetitiveness, imaginative thinness, and shapelessness.”

And Harold Bloom’s admonition to embrace the anxiety of influence crops up, if from another source:

“Immature writers imitate, said Eliot, and mature writers steal: you can pocket the odd phrase, but only if you then do something with it, something ‘mature’. The rightful owner is Shakespeare – so you’d get caught, and quickly, too. This is the Plagiarist’s Dilemma: your writers have to be worth stealing from, and their stuff is famous for that reason …”

And this:

“‘I can’t start a novel’, my stepmother Jane used to say, ‘until I can jot down its theme on the back of an envelope. Just a few words – and it doesn’t matter how trite they are. Appearances are deceptive. Cheats never prosper. Look before you leap … Then I’m ready to begin.’ ‘That would be impossible for me,’ my father Kingsley used to say. ‘I don’t know what its theme is. I’ve got a certain situation or a certain character. Then I just feel my way.’ ‘Well I feel my way too. Once I’ve got going. But I can’t get going until I can at least fool myself that I know what I’m getting going on.’ … For me it’s a journey with a destination but without maps; you have a certain place you want to get to – but you don’t know the way. As you near that goal, though (one year later, or two, or four, or six), you can probably do what Jane did: you can formulate its gist in a single phrase; and that commonplace motto can serve as a touchstone during your final revisions. This is when you begin to sense the salutary pressure to cut … Particular sentences and paragraphs will feel strained and unstable; they seem to be hinting at their own expendability. And now’s the time to consult the back of that envelope: if the passage that disquiets you has no clear bearing on the stated theme – then (with regret, having saved what you can for another day) you should let it go. What you are after, at this stage, is unity.”

These tips are not for everyone. Amis’ hero Saul Bellow, he argues, operated the other way - by finding an individual to know, to adore, and have that insight find its way towards saying something universal.

There are so many tips in the book, no doubt hard earned, it is impossible to quote them all. If you want to learn how to write well, while gaining some insight into a significant literary life, this certainly is the book for you.

Perspective flits in Amis’ world. Sometimes he, the author, is addressing you, the reader directly. Sometimes there is free indirect discourse. Sometimes he is describing his own actions in the third person: ‘Martin did this…’ The most interesting point about these shifts, for us, is that they flow so well. Often you’re barley aware of this happening, or it occurs in a way that just seems to make sense. This, we believe, is a hallmark of - if not genius exactly - a very adept writer.

Another notable feature is the breadth of Amis’ literary range, He pulls in quotes from seemingly everyone - Shakespeare to Elmore Lenoard - in a way that doesn’t detract from the novel, but instead adds value to it. And he has really thought about these people. So when their quotes are presented, or interpretations of their work come up, you really do sit up and take notice.

The Bohemian influence of Amis’ father, Kingsley lived on in Amis. Despite his proletarian affinity, Amis senior was not really one of the working class (see his own autobiography). Due to his reach at both Oxford and the army, he found it easier than most would have to get published, and reach a level of success without the barriers one might face in pursuing the same goals. This level of middle class: modest, but with reach, put both Amis within reach of a layer of celebrity and intellectual London life which would have been out of the reach of most people.

We thought two things were overdone, but to different degrees. Amis seems to place such stock on 9/11 that it became a defining point in his life. Why? This Golem of his mind is of no more significant resonance for him than many, many other people. He places a confusing amount of weight on the tragedy, which seems to resonate throughout the rest of his life. This, for an event that objectively could have been of only limited personal importance begs the question why it became such a dominant theme.

The other is Kingsley and Martin Amis’ affinity for Larkin. Amis and his father placed Larkin on such a pedestal it is difficult not to see a level of obsequiousness in it. In a similar way, it appears Martin Amis did the same thing to Saul Bellow. We understand the desire to be reverential of these heroes - Bellow and Larkin are favourites of ours, too. But the kid gloves with which they were dealt became surprisingly cloying at times. That said, the Larkin relationship takes a slightly surprising and effacing turn at one point in this book, so perhaps he was not quite as venerated as Bellow became for him.

The end featured an apology to Elizabeth Jane Howard which we very much enjoyed reading. This was a poignant end, since Martin did not manage to make it (the apology) while she was alive.

Overall

Inside Story is a roman à clef where you are certain you possess the keys, but aren’t quite sure which doors they open, working out how to read this novel is part of its challenge.

This confusing, lengthy and involuted book is really a masterpiece. It has layers of advice and meaning that cannot be absorbed in one sitting. Although it is a roman à clef where you are certain you possess the keys, but aren’t quite sure which doors they open, working out how to read this novel is part of its challenge. Its fun. Its latent quality. And for that reason it is a Latent Book Club favourite.

We close with a saying from Amis himslelf, expressing a sentiment about writers that, though one feels it, is rarely expressed:

“To be a poet, to be a writer, you have to be continuously surprised. You have to have something of the fucking old fool in you. Borges, in his long conversation with the Paris Review, at one point spoke with bafflement about all the people who simply fail to notice the mystery and glamour of the observable world. In a sentence that stands out for its homeliness, he said, ‘They take it all for granted.’ They accept the face value of things … Writers take nothing for granted. See the world with ‘your original eyes’, ‘your first heart’, but don’t play the child, don’t play the innocent – don’t examine an orange like a caveman toying with an iPhone. You know more than that, you know better than that. The world you see out there is ulterior: it is other than what is obvious or admitted. So never take a single speck of it for granted. Don’t trust anything, don’t even dare to get used to anything. Be continuously surprised. Those who accept the face value of things are the true innocents, endearingly and in a way enviably rational: far too rational to attempt a novel or a poem. They are unsuspecting – yes, that’s it. They are the unsuspecting.”

Before you go…

Read Our Catalogue of Long Form Literary Criticism

If you like long form literary criticism, be sure to check out our previous reviews:

Booker Prize Winner Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of The Day (As an audiobook)

Pulitzer Prize and Nobel Prize for Literature winner Saul Bellow’s Humboldt’s Gift,

Breakout Australian Novelist Amy Taylor’s Search History

Miles Franklin Award Nominee Robbie Arnott’s Limberlost (As an audiobook)

Subscribe to The Latent Book Club for free

Love Amis? Whether Kinglsey is the king, or Martin is the man, get more reviews by them and others like them each week, for free, by subscribing to The Latent Book Club.