There are, we are told, only two dates you need to know in British History: 1055 and 55 BC. But is this actually true?

There are, 1066 And All That tells us, only two dates you need to know in British History: 1055 and 55 BC. Everything else that has happened - throughout the course of history - are just things you may, or may not, happen to remember. And because history is only things you happen to remember, there really are only two dates you need to know: 1066 and 55 BC. At least so goes the argument in W.C. Sellar (an unfortunate two first initials) and R.J. Yeatman’s once beloved, but now somewhat arcane, 1066 And All That.

The one thing the modern reader wants to know, however: is 1066 worth your time? And the answer, unfortunately, is… probably not, at least for most people. 1066… was published in 1930, for a decidedly British, largely public school (ie privately) educated schoolboy, and this comes across in spades. The book employs intentional distortion of historical events, dates, and facts, to create a humorous narrative, but this comes at the price of substance. This is fine if you already know the history that is being satirised. But probably not if you don’t. Here is a typical example of 1066’s… high handedness:

For a long time before the Civil War, however, Charles had been quarrelling with the Roundheads about what was right. Charles explained that there was a doctrine called the Divine Right of Kings, which said that :

(a) He was King, and that was right.

(b( Kings were divine, and that was right.

(c) Kings were right, and that was right.

(d) Everything was all right.

As we can see, the book itself is satire, done slightly oddly. It deliberately confuses names, dates and locations of historical figures with homonyms: eg. Robert Stephenson, steam locomotive pioneer, becomes in 1066… Robert Louis Stephenson, famously the author of Treasure Island and The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. In the same vein William III (William of Orange) and his wife Mary becomes Williamanmary. Simultaneously, it weaves in innumerable poetry (particularly references to Latent Book Club favourite Thomas Gray, Keats and Byron) and literary allusions which are likely to bypass a modern audience.

1066.. is also filled to the brim with mostly serviceable but sometimes downright awful puns, which makes 1066… last longer in the memory, but does not make it a work one can readily take seriously. This may be no bad thing, however, since the reader was certainly never meant to.

So what can we take from 1066? Two things for a start:

1066

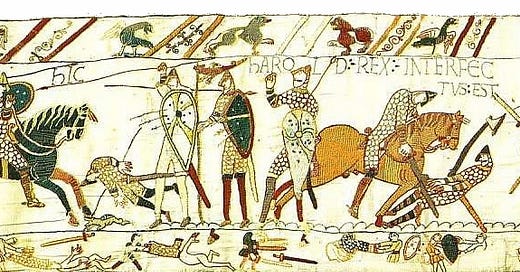

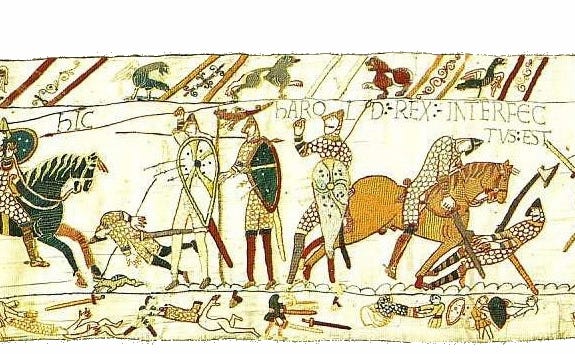

1066 is, naturally, the year of the Battle of Hastings. This seismic event marked the end of the Anglo-Saxon Kings of England, and the commencement of Norman (ie French) rule in England. 1066 was such a moment in English history that its effects are still felt to this day, not only in the proliferation of Norman architecture around the UK, in the form of churches and castles, but moreover it a completely overhauled society. The former aristocracy was removed. Slaves were freed. Systems of language and law were forever changed. For instance, the modern system of English property law is still built on the \French conception, and common-law derived legal jurisdictions across the world are still peppered with French terminology, such as ‘autrefois acquit’ (crime), ‘estoppel’ (contract), and ‘voir dire’ (trials of issues).

The Norman era didn’t really end, more fizzled out as the Plantagenets (the English Normans) ultimately gave way to the Tudors, but the effects of 1066 remain firmly implanted in England’s collective consciousness.

55 BC

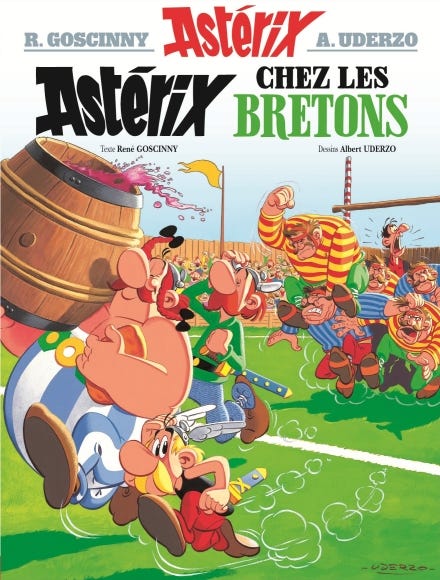

55 BC was the date of the first Roman invasion of England.

In 55 BC, Caesar invaded Britain for the first time. This turned out to be more of a failed reconnaissance mission than a full scale invasion, as under preparedness on the Roman side, and surprising levels of resistance on the side of the Britons meant the invasion was abandoned. The invasion proper took place the following year (54 BC) leaving Britain as a Roman tributary and vassal state; only to be conquered fully by the Empire in AD 43 under Emperor Claudius. Britain remained under Roman rule until 410 AD, when instability within the Empire, coupled with internal and external tensions meant it was difficult for the Empire to hang on to its province. Finally, the Rescript of Honorius meant that Roman troops in England would no longer be paid, and the English were, effectively, responsible for their own defence, which has been interpreted as a tacit acceptance of self-rule.

And All That..

Having dealt with the two key dates, what is the rest of the book about? Well, it charts (poorly and inaccurately) the English monarchy, and its history, from Caesar to the early 20th century. In doing so, it lampoons classic history teaching that a British schoolboy probably would have had to contend with. It contains several layers of high humour, including (impossible) farcical exam papers which are certainly redolent of that period. It also employs a fairly classic running gag, labelling anything that advances the cause of British history, even where the actual event was pretty awful, as ‘That was a ‘Good Thing’. The repetition of this device makes it funnier the more it is used, particularly when it precedes something truly horrific.

In essence, 1066… is a witty and clever parody that uses humour to explicate historical events, personalities, and the quirks of historical education. It is perhaps most impressive for its enduring popularity —apparently, it has never been out of print— and its ability to entertain and make readers think about history in a different, more light-hearted way.

In many ways 1066… was a pioneer itself of the comedic history genre which paved the way for other contemporary works, ie Terry Deary’s Horrible Histories to step in and take over the role of providing some lighthearted history lessons for today’s schoolchildren.

And the fact that other works have eclipsed is function is symptomatic of the problems with 1066… to a modern audience. The language is tired, the humour is arcane, and it is unlikley the average reader has enough history of the type required by 1066 to differentiate between other than the more glaring portions of fact and satire the book doles out. Consequently, therefore, the book falls flat. Funny in parts, but whether 1066… itself remains ‘A Good Thing’ is rather less certain.

Thanks for Reading! Before you go…

Read Our Catalogue of Long Form Literary Criticism

If you like long form literary criticism, be sure to check out our previous reviews:

Booker Prize Winner Iris Murdoch’s The Sea, The Sea

Booker Prize Winner Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of The Day ,

Pulitzer Prize and Nobel Prize for Literature winner Saul Bellow’s Humboldt’s Gift,

Breakout Australian Novelist Amy Taylor’s Search History

Miles Franklin Award Nominee Robbie Arnott’s Limberlost

Or see of our full range of literary criticism in our archive.

Subscribe to The Latent Book Club for free

A fan of Updike? Make sure you don’t more reviews and other great recommendations and analysis by subscribing, for free, to The Latent Book Club.